HE

forces under the command of Prince Mihdi-Quli Mirza meanwhile had recovered from

the state of utter demoralisation into which they had sunk, and were now diligently

preparing to renew their attack upon the occupant s of the fort of Tabarsi. The

latter found themselves again encompassed by a numerous host, at the head of which

marched Abbas-Quli Khan-i- Larijani and Sulayman Khan-i-Afshar-i-Shahriyari, who,

together with several regiments of infantry and cavalry , had hastened to reinforce

the company of the prince's soldiers.(1) Their combined forces encamped

in the neighbourhood of the fort,(2) and proceeded to erect a series

of seven barricades around it. With the utmost arrogance, they sought at first

to display the extent of the forces at their command, and indulged with increasing

zest in the daily exercise of their arms.

HE

forces under the command of Prince Mihdi-Quli Mirza meanwhile had recovered from

the state of utter demoralisation into which they had sunk, and were now diligently

preparing to renew their attack upon the occupant s of the fort of Tabarsi. The

latter found themselves again encompassed by a numerous host, at the head of which

marched Abbas-Quli Khan-i- Larijani and Sulayman Khan-i-Afshar-i-Shahriyari, who,

together with several regiments of infantry and cavalry , had hastened to reinforce

the company of the prince's soldiers.(1) Their combined forces encamped

in the neighbourhood of the fort,(2) and proceeded to erect a series

of seven barricades around it. With the utmost arrogance, they sought at first

to display the extent of the forces at their command, and indulged with increasing

zest in the daily exercise of their arms.

The scarcity of water had, in the meantime,

compelled those who were besieged to dig a well within the enclosure of the fort.

On the day the work was to be completed, the eighth day of the month of Rabi'u'l-Avval,(1) Mulla Husayn, who was watching his companions perform

this task, remarked: "To-day we shall have all the water we require for our bath.

Cleansed of all earthly defilements, we shall seek the court of the Almighty,

and shall hasten to our eternal abode. Whoso is willing to partake of the cup

of martyrdom, let him prepare himself and wait for the hour when he can seal with

his life-blood his faith in his Cause. This night, ere the hour of dawn, let those

who wish to join me be ready to issue forth from behind these walls and, scattering

once again the dark forces which have beset our path, ascend untrammelled to the

heights of glory."

The scarcity of water had, in the meantime,

compelled those who were besieged to dig a well within the enclosure of the fort.

On the day the work was to be completed, the eighth day of the month of Rabi'u'l-Avval,(1) Mulla Husayn, who was watching his companions perform

this task, remarked: "To-day we shall have all the water we require for our bath.

Cleansed of all earthly defilements, we shall seek the court of the Almighty,

and shall hasten to our eternal abode. Whoso is willing to partake of the cup

of martyrdom, let him prepare himself and wait for the hour when he can seal with

his life-blood his faith in his Cause. This night, ere the hour of dawn, let those

who wish to join me be ready to issue forth from behind these walls and, scattering

once again the dark forces which have beset our path, ascend untrammelled to the

heights of glory."  That same afternoon, Mulla Husayn performed

his ablutions, clothed himself in new garments, attired his head with the Bab's

turban, and prepared for the approaching encounter. An undefinable joy illumined

his face. He serenely alluded to the hour of his departure, and continued to his

last moments to animate the zeal of his companions. Alone with Quddus, who so

powerfully reminded him of his Beloved, he poured forth, as he sat at his feet

in the closing moments of his earthly life, all that an enraptured soul could

no longer restrain. Soon after midnight, as soon as the morning-star had risen,

the star that heralded to him the dawning light of eternal reunion with his Beloved,

he started to his feet and, mounting his charger, gave the signal that the gate

of the fort be opened. As he rode out at the head of three hundred and thirteen

of his companions to meet the enemy, the cry of "Ya Sahibu'z-Zaman!"(2) again broke forth, a cry so intense and powerful that

forest, fort, and camp vibrated to its resounding echo.

That same afternoon, Mulla Husayn performed

his ablutions, clothed himself in new garments, attired his head with the Bab's

turban, and prepared for the approaching encounter. An undefinable joy illumined

his face. He serenely alluded to the hour of his departure, and continued to his

last moments to animate the zeal of his companions. Alone with Quddus, who so

powerfully reminded him of his Beloved, he poured forth, as he sat at his feet

in the closing moments of his earthly life, all that an enraptured soul could

no longer restrain. Soon after midnight, as soon as the morning-star had risen,

the star that heralded to him the dawning light of eternal reunion with his Beloved,

he started to his feet and, mounting his charger, gave the signal that the gate

of the fort be opened. As he rode out at the head of three hundred and thirteen

of his companions to meet the enemy, the cry of "Ya Sahibu'z-Zaman!"(2) again broke forth, a cry so intense and powerful that

forest, fort, and camp vibrated to its resounding echo.  Mulla Husayn first charged the barricade which

was defended by Zakariyyay-i-Qadi-Kala'i, one of the enemy's most valiant officers.

Within a short space of time, he had broken

Mulla Husayn first charged the barricade which

was defended by Zakariyyay-i-Qadi-Kala'i, one of the enemy's most valiant officers.

Within a short space of time, he had broken

|

through that barrier, disposed of its commander, and scattered his men. Dashing forward with the same swiftness and intrepidity, he overcame the resistance of both the second and third barric ades, diffusing, as he advanced, despair and consternation among his foes. Undeterred by the bullets which rained continually upon him and his companions, they pressed forward until the remaining barricades had all been captured and overthrown. In the midst of the tumult which ensued, Abbas-Quli Khan-i-Larijani had climbed a tree, and, hiding himself in its branches, lay waiting in ambush for his opponents. Protected by the darkness which surrounded him, he was able to follow from his hiding place the movements of Mulla Husayn and his companions, who were exposed to the fierce glare of the conflagration which they had raised. The steed of Mulla Husayn suddenly became entangled in the rope of an adjoining tent, and ere he was able to extricate himself, he was struck in the breast by a bullet from his treacherous assailant. Though the shot was successful, Abbas-Quli Khan was unaware of the identity of the horseman he had wounded. Mulla Husayn, who was bleeding profusely, dis mounted from his horse, staggered a few steps, and, unable to proceed further, fell exhausted upon the ground. Two of his young companions, of Khurasan, Quli, and Hasan, came to his rescue and bore him to the fort.(1) |

I have heard the following account from Mulla

Sadiq and Mulla Mirza Muhammad-i-Furughi: "We were among those who had remained

in the fort with Quddus. As soon as Mulla Husay n, who seemed to have lost consciousness,

was brought in, we were ordered to retire. `Leave me alone with him,' were the

words of Quddus as he bade Mirza Muhammad-Baqir close the door and refuse admittance

to anyone desiring to see him. `There are c ertain confidential matters which

I desire him alone to know.' We were amazed a few moments later when we heard

the voice of Mulla Husayn replying to questions from Quddus. For two hours they

continued to converse with each other. We were surprised to see Mirza Muhammad-Baqir

so greatly agitated. `I was watching Quddus,' he subsequently informed us, `through

a fissure in the door. As soon as he called his name, I saw Mulla Husayn arise

and seat himself, in his customary manner, on bended kne es beside him. With bowed

head and downcast eyes, he listened to every word that fell from the lips of Quddus,

and answered his questions. "You have hastened the hour of your departure," I

was able to hear Quddus remark, "and have abandoned me to th e mercy of my foes.

Please God, I will ere long join you and taste the sweetness of heaven's ineffable

delights." I was able to gather the following words uttered by Mulla Husayn: "May

my life be a ransom for you. Are you well pleased with me?"'

I have heard the following account from Mulla

Sadiq and Mulla Mirza Muhammad-i-Furughi: "We were among those who had remained

in the fort with Quddus. As soon as Mulla Husay n, who seemed to have lost consciousness,

was brought in, we were ordered to retire. `Leave me alone with him,' were the

words of Quddus as he bade Mirza Muhammad-Baqir close the door and refuse admittance

to anyone desiring to see him. `There are c ertain confidential matters which

I desire him alone to know.' We were amazed a few moments later when we heard

the voice of Mulla Husayn replying to questions from Quddus. For two hours they

continued to converse with each other. We were surprised to see Mirza Muhammad-Baqir

so greatly agitated. `I was watching Quddus,' he subsequently informed us, `through

a fissure in the door. As soon as he called his name, I saw Mulla Husayn arise

and seat himself, in his customary manner, on bended kne es beside him. With bowed

head and downcast eyes, he listened to every word that fell from the lips of Quddus,

and answered his questions. "You have hastened the hour of your departure," I

was able to hear Quddus remark, "and have abandoned me to th e mercy of my foes.

Please God, I will ere long join you and taste the sweetness of heaven's ineffable

delights." I was able to gather the following words uttered by Mulla Husayn: "May

my life be a ransom for you. Are you well pleased with me?"'  "A long time elapsed before Quddus bade Mirza

Muhammad-Baqir open the door and admit his companions. `I have bade my last farewell

to him,' he said, as we entered the room. `Things which previously I deeme d it

unallowable to utter I have now shared with him.' We found on

our arrival that Mulla Husayn had expired. A faint smile still lingered upon his

face. Such was the peacefulness of his countenance that he seemed to have fallen

asleep. Quddus at tended to his burial, clothed him in his own shirt, and gave

instructions to lay him to rest to the south of, and adjoining, the shrine of

Shaykh Tabarsi.(1) `Well is

it with you to have remained to yo ur last hour faithful to the Covenant

"A long time elapsed before Quddus bade Mirza

Muhammad-Baqir open the door and admit his companions. `I have bade my last farewell

to him,' he said, as we entered the room. `Things which previously I deeme d it

unallowable to utter I have now shared with him.' We found on

our arrival that Mulla Husayn had expired. A faint smile still lingered upon his

face. Such was the peacefulness of his countenance that he seemed to have fallen

asleep. Quddus at tended to his burial, clothed him in his own shirt, and gave

instructions to lay him to rest to the south of, and adjoining, the shrine of

Shaykh Tabarsi.(1) `Well is

it with you to have remained to yo ur last hour faithful to the Covenant

No less than ninety of the companions were

wounded that night, most of whom succumbed. From the day of their arrival at Barfurush

to the day they were first attacked, which fell on the twelfth of Dhi'l-Qa'dih

in the year 1264 A.H.,(1) to the day of the death of Mulla Husayn, which took

place at the hour of dawn on the ninth of Rabi'u'l-Avval in the year 1265 A.H.,(2) the number of martyrs, according to the computation

of Mirza Muhammad-Baqir, had reached a total of seventy-two.

No less than ninety of the companions were

wounded that night, most of whom succumbed. From the day of their arrival at Barfurush

to the day they were first attacked, which fell on the twelfth of Dhi'l-Qa'dih

in the year 1264 A.H.,(1) to the day of the death of Mulla Husayn, which took

place at the hour of dawn on the ninth of Rabi'u'l-Avval in the year 1265 A.H.,(2) the number of martyrs, according to the computation

of Mirza Muhammad-Baqir, had reached a total of seventy-two.  From the time when Mulla Husayn was assailed

by his enemies to the time of his martyrdom was a hundred and sixteen days, a

period rendered memorable by deeds so heroic that even his bitterest foes felt

bound to confess their wonder. On four distinct occasions, he rose to such heights

of courage and power as few indeed could attain. The first encounter took place

on the twelfth of Dhi'l-Qa'dih,(3) in the outskirts of Barfurush;

the second, in the immediate neighbourhood of the fort of Shaykh Tabarsi, on the

fifth day of the month of Muharram,(4) against the forces of Abdu'llah Khan-i-Turkaman; the

third, in Vas-Kas, on the twenty-fifth day of Muharram,(5) directed against the army of Prince

From the time when Mulla Husayn was assailed

by his enemies to the time of his martyrdom was a hundred and sixteen days, a

period rendered memorable by deeds so heroic that even his bitterest foes felt

bound to confess their wonder. On four distinct occasions, he rose to such heights

of courage and power as few indeed could attain. The first encounter took place

on the twelfth of Dhi'l-Qa'dih,(3) in the outskirts of Barfurush;

the second, in the immediate neighbourhood of the fort of Shaykh Tabarsi, on the

fifth day of the month of Muharram,(4) against the forces of Abdu'llah Khan-i-Turkaman; the

third, in Vas-Kas, on the twenty-fifth day of Muharram,(5) directed against the army of Prince

So c omplete and humiliating a rout paralysed

for a time the efforts of the enemy. Five and forty days passed before they could

again reassemble their forces and renew their attack. During these intervening

days, which ended with the day of Naw-Ruz, the intense cold which prevailed induced

them to defer their venture against an opponent that had covered them with so

much reproach and shame. Though their attacks had been suspended, the officers

in charge of the remnants of the imperial army had given strict orders prohibiting

the arrival of all manner of reinforcements at the fort. When the supply of their

provisions was nearly exhausted, Quddus instructed Mirza Muhammad-Baqir to distribute

among his companions the rice which Mulla Husayn had s tored for such time as

might be required. When each had received his portion, Quddus summoned them and

said: "Whoever feels himself strong enough to withstand the calamities that are

soon to befall us, let him remain with us in this fort. And whoev er perceives

in himself the least hesitation and fear, let him betake himself away from this

place. Let him leave immediately ere the enemy has again assembled his forces

and assailed us. The way will soon be barred before our face; we shall very so

on encounter the severest hardship and fall a victim to devastating afflictions."

So c omplete and humiliating a rout paralysed

for a time the efforts of the enemy. Five and forty days passed before they could

again reassemble their forces and renew their attack. During these intervening

days, which ended with the day of Naw-Ruz, the intense cold which prevailed induced

them to defer their venture against an opponent that had covered them with so

much reproach and shame. Though their attacks had been suspended, the officers

in charge of the remnants of the imperial army had given strict orders prohibiting

the arrival of all manner of reinforcements at the fort. When the supply of their

provisions was nearly exhausted, Quddus instructed Mirza Muhammad-Baqir to distribute

among his companions the rice which Mulla Husayn had s tored for such time as

might be required. When each had received his portion, Quddus summoned them and

said: "Whoever feels himself strong enough to withstand the calamities that are

soon to befall us, let him remain with us in this fort. And whoev er perceives

in himself the least hesitation and fear, let him betake himself away from this

place. Let him leave immediately ere the enemy has again assembled his forces

and assailed us. The way will soon be barred before our face; we shall very so

on encounter the severest hardship and fall a victim to devastating afflictions."

The very night Quddus had

given this warning, a siyyid from Qum, Mirza Husayn-i-Mutavalli, was moved to

betray his companion s. "Why is it," he wrote to Abbas-Quli Khan-i-Larijani, "that

you have left unfinished the work

The very night Quddus had

given this warning, a siyyid from Qum, Mirza Husayn-i-Mutavalli, was moved to

betray his companion s. "Why is it," he wrote to Abbas-Quli Khan-i-Larijani, "that

you have left unfinished the work

He had just risen from his bed when, at the hour

of sunrise, the siyyid brough t him the letter. The news of the death of Mulla

Husayn nerved him to a fresh resolve. Fearing

He had just risen from his bed when, at the hour

of sunrise, the siyyid brough t him the letter. The news of the death of Mulla

Husayn nerved him to a fresh resolve. Fearing

The day had just broken when he hoisted his standard

(1) and, marching at the head of two regiments of infa ntry

and cavalry, encompassed the fort and ordered his men to open fire upon the sentinels

who were guarding the turrets. "The betrayer," Quddus informed Mirza Muhammad-Baqir,

who h ad hastened to acquaint him with the gravity of the situation, "has announced

the death of Mulla Husayn to Abbas-Quli Khan. Emboldened by his removal, he is

now determined to storm our stronghold and to secure for himself the honour of

being its sole conqueror. Sally out and, with the aid of eighteen men marching

at your side, administer a befitting chastisement upon the aggressor and his host.

Let him realise that though Mulla Husayn be no more, God's

The day had just broken when he hoisted his standard

(1) and, marching at the head of two regiments of infa ntry

and cavalry, encompassed the fort and ordered his men to open fire upon the sentinels

who were guarding the turrets. "The betrayer," Quddus informed Mirza Muhammad-Baqir,

who h ad hastened to acquaint him with the gravity of the situation, "has announced

the death of Mulla Husayn to Abbas-Quli Khan. Emboldened by his removal, he is

now determined to storm our stronghold and to secure for himself the honour of

being its sole conqueror. Sally out and, with the aid of eighteen men marching

at your side, administer a befitting chastisement upon the aggressor and his host.

Let him realise that though Mulla Husayn be no more, God's

No sooner had Mirza Muhammad-Baqir selected his companions than he ordered

that the gate of the fort be flung ope n. Leaping upon their chargers and raising

the cry of "Ya Sahibu'z- Zaman!" they plunged headlong into the camp of the enemy.

The whole army fled in confusion before so terrific a charge. All but a few were

able to escape. They reached Barfurush ut terly demoralised and laden with shame.

Abbas-Quli Khan was so shaken with fear that he fell from his horse. Leaving,

in his distress, one of his boots hanging from the stirrup, he ran away, half

shod and bewildered, in the direction which the army had taken. Filled with despair,

he hastened to the prince and confessed the ignominious reverse he had sustained.(1)

Mirza Muhammad- Baqir, on his part, emerging together with his eighteen companions

unscathed from that encounter, and holding in his hand the

No sooner had Mirza Muhammad-Baqir selected his companions than he ordered

that the gate of the fort be flung ope n. Leaping upon their chargers and raising

the cry of "Ya Sahibu'z- Zaman!" they plunged headlong into the camp of the enemy.

The whole army fled in confusion before so terrific a charge. All but a few were

able to escape. They reached Barfurush ut terly demoralised and laden with shame.

Abbas-Quli Khan was so shaken with fear that he fell from his horse. Leaving,

in his distress, one of his boots hanging from the stirrup, he ran away, half

shod and bewildered, in the direction which the army had taken. Filled with despair,

he hastened to the prince and confessed the ignominious reverse he had sustained.(1)

Mirza Muhammad- Baqir, on his part, emerging together with his eighteen companions

unscathed from that encounter, and holding in his hand the

So complete a rout immediately brought relief

to the hard-pressed companions. It cemented their unity and reminded them afresh

of the efficacy of that power with which their Faith had endowed them. Their food,

alas, was by this time reduced to the flesh of horses, which they had brought

away with them from the deserted camp of the enemy. With steadfast fortitude they

endured the afflictions which beset them from every side. Their hearts were set

on the wishes of Quddus; all else mattered but little. Neither the severity of

their distress nor the continual threats of the enemy could cause them to deviate

a hairbreadth from the path which their departed companions had so heroically

trodden. A few were found who subsequently faltered in t he darkest hour of adversity.

The faint-heartedness which this negligible element was compelled to betray paled,

however, into insignificance before the radiance which the mass of their stouthearted

companions shed in the hour of realised doom.

So complete a rout immediately brought relief

to the hard-pressed companions. It cemented their unity and reminded them afresh

of the efficacy of that power with which their Faith had endowed them. Their food,

alas, was by this time reduced to the flesh of horses, which they had brought

away with them from the deserted camp of the enemy. With steadfast fortitude they

endured the afflictions which beset them from every side. Their hearts were set

on the wishes of Quddus; all else mattered but little. Neither the severity of

their distress nor the continual threats of the enemy could cause them to deviate

a hairbreadth from the path which their departed companions had so heroically

trodden. A few were found who subsequently faltered in t he darkest hour of adversity.

The faint-heartedness which this negligible element was compelled to betray paled,

however, into insignificance before the radiance which the mass of their stouthearted

companions shed in the hour of realised doom.

Prince Mihdi-Quli Mirza, who was stationed

in Sari, welcomed with keen delight the news of the defeat that had overtaken

the forces under the immediate command of his colleague Abbas-Quli Khan. Though

himself desirous of extirpating the band that had sought shelter behind the walls

of the fort, he rejoiced at the knowledge that his rival had failed to secure

the victory which he coveted.(1)

He wrote immediately to Tihran and demanded that reinforcements in the form of

bomb-shells and camel-artillery, with all the necessary equipments, be despatched

without delay to the neighbourhood of the fort, he being determined, this time,

to effect t he complete subjugation of its obstinate occupants.

Prince Mihdi-Quli Mirza, who was stationed

in Sari, welcomed with keen delight the news of the defeat that had overtaken

the forces under the immediate command of his colleague Abbas-Quli Khan. Though

himself desirous of extirpating the band that had sought shelter behind the walls

of the fort, he rejoiced at the knowledge that his rival had failed to secure

the victory which he coveted.(1)

He wrote immediately to Tihran and demanded that reinforcements in the form of

bomb-shells and camel-artillery, with all the necessary equipments, be despatched

without delay to the neighbourhood of the fort, he being determined, this time,

to effect t he complete subjugation of its obstinate occupants.  Whilst their enemies were preparing for yet another

and still fiercer attack upon their stronghold, the companions of Quddus, utterly

indifferent to the gn awing distress that afflicted them, acclaimed with joy and

gratitude the approach of Naw-Ruz. In the course of that festival, they gave free

vent to their feelings of thanksgiving and praise in return for the manifold blessings

which the Almighty had bestowed upon them. Though oppressed with hunger, they

indulged in songs and merriment, utterly disdaining the danger with which they

were beset. The fort resounded with the ascriptions of glory and praise which,

both in the daytime and in the nig ht-season, ascended from the hearts of that

joyous band. The verse, "Holy, holy, the Lord our God, the Lord of the angels

and the spirit," issued unceasingly from their lips, heightened their enthusiasm,

and reanimated their courage.

Whilst their enemies were preparing for yet another

and still fiercer attack upon their stronghold, the companions of Quddus, utterly

indifferent to the gn awing distress that afflicted them, acclaimed with joy and

gratitude the approach of Naw-Ruz. In the course of that festival, they gave free

vent to their feelings of thanksgiving and praise in return for the manifold blessings

which the Almighty had bestowed upon them. Though oppressed with hunger, they

indulged in songs and merriment, utterly disdaining the danger with which they

were beset. The fort resounded with the ascriptions of glory and praise which,

both in the daytime and in the nig ht-season, ascended from the hearts of that

joyous band. The verse, "Holy, holy, the Lord our God, the Lord of the angels

and the spirit," issued unceasingly from their lips, heightened their enthusiasm,

and reanimated their courage.  All that remained of the cattle they had brought

with them to the fort was a cow which Haji Nasiru'd-Din-i- Qazvini had set aside,

and the milk of which he made into a pudding every day for the table of Quddus.

Unwilling t o

All that remained of the cattle they had brought

with them to the fort was a cow which Haji Nasiru'd-Din-i- Qazvini had set aside,

and the milk of which he made into a pudding every day for the table of Quddus.

Unwilling t o

I have heard Mulla Mirza Muhammad-i-Furughi

testify to the follo wing: "God knows that we had ceased to hunger for food. Our

thoughts were no longer concerned with matters pertaining to our daily bread.

We were so enraptured by the entrancing melody of those verses that, were we to

have continued for years in th at state, no trace of weariness and fatigue could

possibly have dimmed our enthusiasm or marred our gladness. And whenever the lack

of nourishment would tend to sap our vitality and weaken our strength, Mirza Muhammad-Baqir

would hasten to Quddus and acquaint him with our plight. A glimpse of his face,

the magic of his words, as he walked amongst us, would transmute our despondency

into golden joy. We were reinforced with a strength of such intensity that, had

the hosts of our enemies appeared suddenly before us, we felt ourselves capable

of subjugating their forces."

I have heard Mulla Mirza Muhammad-i-Furughi

testify to the follo wing: "God knows that we had ceased to hunger for food. Our

thoughts were no longer concerned with matters pertaining to our daily bread.

We were so enraptured by the entrancing melody of those verses that, were we to

have continued for years in th at state, no trace of weariness and fatigue could

possibly have dimmed our enthusiasm or marred our gladness. And whenever the lack

of nourishment would tend to sap our vitality and weaken our strength, Mirza Muhammad-Baqir

would hasten to Quddus and acquaint him with our plight. A glimpse of his face,

the magic of his words, as he walked amongst us, would transmute our despondency

into golden joy. We were reinforced with a strength of such intensity that, had

the hosts of our enemies appeared suddenly before us, we felt ourselves capable

of subjugating their forces."  On the day of Naw-Ruz, which fell on the twenty-fourth

of Rabi'u'th-Thani in the year 1265 A.H.,(1) Quddus alluded, in a written message to his companions, to

the approach of such trials as would bring in their wake the martyrdom of a considerable

number of his friends. A few days later, an innumerable host,(2)

commanded by Prince Mihdi-Quli

On the day of Naw-Ruz, which fell on the twenty-fourth

of Rabi'u'th-Thani in the year 1265 A.H.,(1) Quddus alluded, in a written message to his companions, to

the approach of such trials as would bring in their wake the martyrdom of a considerable

number of his friends. A few days later, an innumerable host,(2)

commanded by Prince Mihdi-Quli

So powerful an appeal could not fail to breathe

confidence into the hear ts of those who heard it. A few, however, whose countenances

betrayed vacillation and fear, were seen huddled together in a sheltered corner

of the fort, viewing with envy and surprise the zeal that animated their companions.(1)

So powerful an appeal could not fail to breathe

confidence into the hear ts of those who heard it. A few, however, whose countenances

betrayed vacillation and fear, were seen huddled together in a sheltered corner

of the fort, viewing with envy and surprise the zeal that animated their companions.(1)

The army of Prince Mihdi-Quli Mirza continued

for a few days to fire in the direction of the fort. His men were surprised to

find that the booming of their guns had failed to silence the voice of prayer

and the acclamations of joy which the besieged raised in answer to their threats.

Instead of the unconditional surrender which they expected, the call of the muadhdhin,(1) the chanting of the verses of the

Qur'an, and the chorus of gladsome voices intoning hymns of thanksgiving and praise

reached their ears without ceasing.

The army of Prince Mihdi-Quli Mirza continued

for a few days to fire in the direction of the fort. His men were surprised to

find that the booming of their guns had failed to silence the voice of prayer

and the acclamations of joy which the besieged raised in answer to their threats.

Instead of the unconditional surrender which they expected, the call of the muadhdhin,(1) the chanting of the verses of the

Qur'an, and the chorus of gladsome voices intoning hymns of thanksgiving and praise

reached their ears without ceasing.  Exasperated by these evidences of unquenchable

fervour and impelled by a burning desire to extinguish the enthusiasm which swelled

within the breasts of his opponents, Ja'far- quli Khan erected a tower, upon which

he stationed his cannon,(2) and from that eminence directed his fire into the heart

of the fort. Quddus immediately summoned Mirza Muhammad-Baqir and instructed him

to sally again and inflict upon the "bo astful newcomer" a humiliation no less

crushing than the one which Abbas-Quli Khan had suffered.

Exasperated by these evidences of unquenchable

fervour and impelled by a burning desire to extinguish the enthusiasm which swelled

within the breasts of his opponents, Ja'far- quli Khan erected a tower, upon which

he stationed his cannon,(2) and from that eminence directed his fire into the heart

of the fort. Quddus immediately summoned Mirza Muhammad-Baqir and instructed him

to sally again and inflict upon the "bo astful newcomer" a humiliation no less

crushing than the one which Abbas-Quli Khan had suffered.

Mirza Muhammad-Baqir again

ordered eighteen of his companions to hurry to their steeds and follow him. The

gates of the fort wer e thrown open, and the cry of "Ya Sahibu'z-Zaman!"--fiercer

and more thrilling than ever--diffused panic and consternation in the ranks of

the enemy. Ja'far-Quli Khan, with thirty of his men, fell before the sword of

their adversary, who rushed to th e tower, captured the guns, and hurled them

to the ground. Thence they threw themselves upon the barricade which had been

erected, demolished a number of them, and would, but for the approaching darkness,

have captured and destroyed the rest.

Mirza Muhammad-Baqir again

ordered eighteen of his companions to hurry to their steeds and follow him. The

gates of the fort wer e thrown open, and the cry of "Ya Sahibu'z-Zaman!"--fiercer

and more thrilling than ever--diffused panic and consternation in the ranks of

the enemy. Ja'far-Quli Khan, with thirty of his men, fell before the sword of

their adversary, who rushed to th e tower, captured the guns, and hurled them

to the ground. Thence they threw themselves upon the barricade which had been

erected, demolished a number of them, and would, but for the approaching darkness,

have captured and destroyed the rest.  Triumphant and unhurt, they repaired to the

fort, carrying back with them a number of the stoutest and best-fed stallions

which had been left behind. A few days elapsed during which there was no sign

of a counter -attack.(1) A sudden

explosion in one of the ammunition stores of the enemy, which had caused the death

of several artillery officers and a number of their fellow-combatants, forced

them for one whole month to suspend their attacks upon the garrison.(2) This lull enabled a number

of the companions to emerge occasionally from their stronghold and gather such

grass as they could find in the field as the only means wherewith to

Triumphant and unhurt, they repaired to the

fort, carrying back with them a number of the stoutest and best-fed stallions

which had been left behind. A few days elapsed during which there was no sign

of a counter -attack.(1) A sudden

explosion in one of the ammunition stores of the enemy, which had caused the death

of several artillery officers and a number of their fellow-combatants, forced

them for one whole month to suspend their attacks upon the garrison.(2) This lull enabled a number

of the companions to emerge occasionally from their stronghold and gather such

grass as they could find in the field as the only means wherewith to

The month of Jamadiyu'th-Thani(2) had just begun when the artillery of the enemy was heard

again discharging its showers of balls upon the fort. Simultaneously w ith the

booming of the cannons, a detachment of the army, headed by a number of officers

and consisting of several regiments of infantry and cavalry, rushed to storm it.

The sound of their approach impelled Quddus to summon promptly his valiant lieu

tenant, Mirza Muhammad-Baqir, and to bid him emerge with thirty-six of his companions

and repulse their attack.

The month of Jamadiyu'th-Thani(2) had just begun when the artillery of the enemy was heard

again discharging its showers of balls upon the fort. Simultaneously w ith the

booming of the cannons, a detachment of the army, headed by a number of officers

and consisting of several regiments of infantry and cavalry, rushed to storm it.

The sound of their approach impelled Quddus to summon promptly his valiant lieu

tenant, Mirza Muhammad-Baqir, and to bid him emerge with thirty-six of his companions

and repulse their attack.

Mirza Muhammad-Baqir once

more leaped on horseback and, wit h the thirty-six companions whom he had selected,

confronted and scattered the forces which had beset him. He carried with him,

as he re- entered the gate, the banner which an alarmed enemy had abandoned as

soon as the reverberating cry of "Ya Sahibu' z-Zaman!" had been raised. Five of

his companions suffered martyrdom in the course of that engagement, all of whom

he bore to the fort and interred in one tomb close to the resting place of their

fallen brethren.

Mirza Muhammad-Baqir once

more leaped on horseback and, wit h the thirty-six companions whom he had selected,

confronted and scattered the forces which had beset him. He carried with him,

as he re- entered the gate, the banner which an alarmed enemy had abandoned as

soon as the reverberating cry of "Ya Sahibu' z-Zaman!" had been raised. Five of

his companions suffered martyrdom in the course of that engagement, all of whom

he bore to the fort and interred in one tomb close to the resting place of their

fallen brethren.  Prince Mihdi-Quli Mirza,

astounded by this further evidence of the inexhaustible vitality of his opponents,

took counsel with the chiefs of his staff, urging them to devise such means as

would enable him to bring that costly enterprise to a s peedy end. For three days

he deliberated with them, and finally came to the conclusion that the most advisable

course to take would be to suspend all manner of hostilities for a few days in

the hope that the besieged, exhausted with hunger and goaded by despair, would

decide to emerge from their retreat and submit to an unconditional surrender.

Prince Mihdi-Quli Mirza,

astounded by this further evidence of the inexhaustible vitality of his opponents,

took counsel with the chiefs of his staff, urging them to devise such means as

would enable him to bring that costly enterprise to a s peedy end. For three days

he deliberated with them, and finally came to the conclusion that the most advisable

course to take would be to suspend all manner of hostilities for a few days in

the hope that the besieged, exhausted with hunger and goaded by despair, would

decide to emerge from their retreat and submit to an unconditional surrender.

As the prince was waiting for the consummation of the plan he had conceived,

there arrived from Tihran a messenger

As the prince was waiting for the consummation of the plan he had conceived,

there arrived from Tihran a messenger

I have heard Aqay-i-Kalim

give the followi ng account, as related to him by that same messenger whom he

met in Tihran: "`I saw,' the messenger informed me, `Mulla Mihdi appear above

the wall of the fort, his countenance revealing an expression of stern resolve

that baffled description. He l ooked as fierce as a lion, his sword was girded

on over a long white shirt after the manner of the Arabs, and he had a white kerchief

around his head. "What is it that you seek?" he impatiently enquired. "Say it

quickly, for I fear that my master wi ll summon me and find me absent." The determination

that glowed in his eyes confused me. I was dumbfounded at his looks and manner.

The thought suddenly flashed through my mind that I would awaken a dormant sentiment

in his heart. I reminded him o f his infant child, Rahman, whom he had left behind

in the village, in his eagerness to enlist under the standard of Mulla Husayn.

In his great affection for the child, he had specially composed a poem which he

chanted as he rocked his cradle and lul led him to sleep. "Your beloved Rahman,"

I said, "longs for the affection which you once lavished upon him. He is alone

and forsaken, and yearns to see you." "Tell him from me," was the father's instant

reply, "that the love of the true Rahman,(2) a love that transcends all

earthly affections, has so filled my heart that it has left no place for any other

it love besides His." The poignancy with which he uttered these words brought

tears to my eyes. "Accursed," I indignantly exclaimed, "be those who consider

you and your fellow-disciples as having strayed from the path of God!"

I have heard Aqay-i-Kalim

give the followi ng account, as related to him by that same messenger whom he

met in Tihran: "`I saw,' the messenger informed me, `Mulla Mihdi appear above

the wall of the fort, his countenance revealing an expression of stern resolve

that baffled description. He l ooked as fierce as a lion, his sword was girded

on over a long white shirt after the manner of the Arabs, and he had a white kerchief

around his head. "What is it that you seek?" he impatiently enquired. "Say it

quickly, for I fear that my master wi ll summon me and find me absent." The determination

that glowed in his eyes confused me. I was dumbfounded at his looks and manner.

The thought suddenly flashed through my mind that I would awaken a dormant sentiment

in his heart. I reminded him o f his infant child, Rahman, whom he had left behind

in the village, in his eagerness to enlist under the standard of Mulla Husayn.

In his great affection for the child, he had specially composed a poem which he

chanted as he rocked his cradle and lul led him to sleep. "Your beloved Rahman,"

I said, "longs for the affection which you once lavished upon him. He is alone

and forsaken, and yearns to see you." "Tell him from me," was the father's instant

reply, "that the love of the true Rahman,(2) a love that transcends all

earthly affections, has so filled my heart that it has left no place for any other

it love besides His." The poignancy with which he uttered these words brought

tears to my eyes. "Accursed," I indignantly exclaimed, "be those who consider

you and your fellow-disciples as having strayed from the path of God!"

As soon as he had joined his companions, Mulla

Mihdi conveyed the prince's message to them. On the afternoon of that same day,

Siyyid Mirza Husayn-i-Mutavalli, accompanied by his servant, left the fort and

went directly to join the prince in his camp. The next day, Rasul-i- Bahnimiri

and a few other of his companions, unable to resist the ravages of famine, and

encouraged by the exp licit assurances

As soon as he had joined his companions, Mulla

Mihdi conveyed the prince's message to them. On the afternoon of that same day,

Siyyid Mirza Husayn-i-Mutavalli, accompanied by his servant, left the fort and

went directly to join the prince in his camp. The next day, Rasul-i- Bahnimiri

and a few other of his companions, unable to resist the ravages of famine, and

encouraged by the exp licit assurances

During the few days that elapsed after that

incident, the enemy, still encamped in the neighbourhood of the fort, refrained

from any act of hostility towards Quddus and his companions. On Wednesday morning,

the sixteenth of Jamadiyu'th-Thani,(1) an emissary of the prince arrived at the fort and requested

that two representatives be delegated by the besieged to conduct confidential

negotiations with them in the hope of ar riving at a peaceful settlement of the

issues outstanding between them.(2)

During the few days that elapsed after that

incident, the enemy, still encamped in the neighbourhood of the fort, refrained

from any act of hostility towards Quddus and his companions. On Wednesday morning,

the sixteenth of Jamadiyu'th-Thani,(1) an emissary of the prince arrived at the fort and requested

that two representatives be delegated by the besieged to conduct confidential

negotiations with them in the hope of ar riving at a peaceful settlement of the

issues outstanding between them.(2)

Accordingly, Quddus instructed

Mulla Yusuf-i-Ardibili and Siyyid Riday-i-Khurasani to act as his representatives,

and bade them inform the prince of his readiness to accede to his wish. Mihdi-Quli

Mirza courteously received them, and invited them to partake of the tea which

he had prepared. "We should," they said, as they decline d his offer, "feel it

to be an act of disloyalty on our part were we to partake of either meat or drink

whilst our beloved leader languishes worn and famished in the fort." "The hostilities

between us," the prince remarked, "have been unduly prolonge d. We, on both sides,

have fought long and suffered grievously. It is my fervent wish to achieve an

amicable settlement of our differences." He took hold of a copy of the Qur'an

that lay beside him, and wrote, with his own hand, in confirmation of his statement,

the following words on the margin of the opening Surih: "I swear by this most

holy Book, by the righteousness of God who has revealed it, and the Mission of

Him who was inspired with its verses, that I cherish no other purpose than to

promote peace and friendliness between us. Come forth from your stronghold and

rest assured that no hand will be stretched forth against you. You yourself

Accordingly, Quddus instructed

Mulla Yusuf-i-Ardibili and Siyyid Riday-i-Khurasani to act as his representatives,

and bade them inform the prince of his readiness to accede to his wish. Mihdi-Quli

Mirza courteously received them, and invited them to partake of the tea which

he had prepared. "We should," they said, as they decline d his offer, "feel it

to be an act of disloyalty on our part were we to partake of either meat or drink

whilst our beloved leader languishes worn and famished in the fort." "The hostilities

between us," the prince remarked, "have been unduly prolonge d. We, on both sides,

have fought long and suffered grievously. It is my fervent wish to achieve an

amicable settlement of our differences." He took hold of a copy of the Qur'an

that lay beside him, and wrote, with his own hand, in confirmation of his statement,

the following words on the margin of the opening Surih: "I swear by this most

holy Book, by the righteousness of God who has revealed it, and the Mission of

Him who was inspired with its verses, that I cherish no other purpose than to

promote peace and friendliness between us. Come forth from your stronghold and

rest assured that no hand will be stretched forth against you. You yourself

He affixed his seal to his statement and,

delivering the Qur'an into the hands of Mulla Yusuf, asked him to convey his greetings

to his leader and to present him this formal and written assurance. "I will,"

he added, "in pursuance of my declaration, despatch to the gate of the fort, this

very afternoon, a number of horses, which I trust he and his leading companions

will acce pt and mount, in order to ride to the neighbourhood of this camp, where

a special tent will have been pitched for their reception. I would request them

to be our guests until such time as I shall be able to arrange for their return,

at my expense, to their homes."

He affixed his seal to his statement and,

delivering the Qur'an into the hands of Mulla Yusuf, asked him to convey his greetings

to his leader and to present him this formal and written assurance. "I will,"

he added, "in pursuance of my declaration, despatch to the gate of the fort, this

very afternoon, a number of horses, which I trust he and his leading companions

will acce pt and mount, in order to ride to the neighbourhood of this camp, where

a special tent will have been pitched for their reception. I would request them

to be our guests until such time as I shall be able to arrange for their return,

at my expense, to their homes."  Quddus received the Qur'an from the hand of

his messenger, kissed it reverently, and said: "O our Lord, decide between us

and between our people with truth; for the best to decide art Thou." (1)

Immediately after, he bade the rest of his companions prepare themselves to leave

the fort. "By our response to their invitation," he told them, "we shall enable

them to demonstrate the sincerity of their intentions."

Quddus received the Qur'an from the hand of

his messenger, kissed it reverently, and said: "O our Lord, decide between us

and between our people with truth; for the best to decide art Thou." (1)

Immediately after, he bade the rest of his companions prepare themselves to leave

the fort. "By our response to their invitation," he told them, "we shall enable

them to demonstrate the sincerity of their intentions."  As the hour of their departure

approached, Quddus attired his head with the green turban which the Bab had sent

to him at the time He sent the one that Mulla Husayn wore on the day of his martyrdom.

At the gate of the fort, they mounted the horses which had been placed at their

disposal, Quddus mounting the favourite steed of the prince which the latter had

sent for his use. His chief companions, among whom were a number of siyyi ds and

learned divines, rode behind him, and were followed by the rest, who marched on

foot, carrying with them all that was left of their arms and belongings. As the

company, who were two hundred and two in number, reached the tent which the prince

had ordered to be pitched for Quddus in the vicinity of the public bath

As the hour of their departure

approached, Quddus attired his head with the green turban which the Bab had sent

to him at the time He sent the one that Mulla Husayn wore on the day of his martyrdom.

At the gate of the fort, they mounted the horses which had been placed at their

disposal, Quddus mounting the favourite steed of the prince which the latter had

sent for his use. His chief companions, among whom were a number of siyyi ds and

learned divines, rode behind him, and were followed by the rest, who marched on

foot, carrying with them all that was left of their arms and belongings. As the

company, who were two hundred and two in number, reached the tent which the prince

had ordered to be pitched for Quddus in the vicinity of the public bath

Soon after their arrival, Quddus emerged from his

tent and, gathering together his companions, addressed them in these words: "You

should show forth exemplary renunciation, for such behaviour on your part will

exalt our Cau se and redound to its glory. Anything short of complete detachment

will but serve to tarnish the purity of its name and to obscure its splendour.

Pray the Almighty to grant that even to your

Soon after their arrival, Quddus emerged from his

tent and, gathering together his companions, addressed them in these words: "You

should show forth exemplary renunciation, for such behaviour on your part will

exalt our Cau se and redound to its glory. Anything short of complete detachment

will but serve to tarnish the purity of its name and to obscure its splendour.

Pray the Almighty to grant that even to your

A few hours after sunset, they were served with

dinner brought from the camp of the prince. The food that was offered them in

separate trays, each of which was assign ed to a group of thirty companions, was

poor and scanty. "Nine of us," those who were with Quddus subsequently related,

"were summoned by our leader to partake of the dinner which had been served in

his tent. As he refused to taste it, we too, foll owing his example, refrained

from eating. The attendants who waited upon us were delighted to partake of the

dishes which we had refused to touch, and devoured their contents with appreciation

and avidity." A few of the companions

A few hours after sunset, they were served with

dinner brought from the camp of the prince. The food that was offered them in

separate trays, each of which was assign ed to a group of thirty companions, was

poor and scanty. "Nine of us," those who were with Quddus subsequently related,

"were summoned by our leader to partake of the dinner which had been served in

his tent. As he refused to taste it, we too, foll owing his example, refrained

from eating. The attendants who waited upon us were delighted to partake of the

dishes which we had refused to touch, and devoured their contents with appreciation

and avidity." A few of the companions

At daybreak a messenger ar rived, summoning Mirza

Muhammad-Baqir to the presence of the prince. With the consent of Quddus, he responded

to that invitation, and returned an hour later, informing his chief that the prince

had, in the presence of Sulayman Khan-i-Afshar, reiterat ed the assurances he

had given, and had treated him with great consideration and kindness. "`My oath,'

he assured me," Mirza Muhammad-Baqir explained, "`is irrevocable and sacred.'

He cited the case of Ja'far-Quli Khan, who, notwithstanding his sha meless massacre

of thousands of soldiers of the imperial army, in the course of the insurrection

fomented by the Salar, was pardoned by his sovereign and promptly invested with

fresh honours by Muhammad Shah. To-morrow the prince intends to accompany you

in the morning to the public bath, from whence he will proceed to your tent, after

which he will provide the horses required to convey the entire company to Sang-Sar,

from where they will disperse, some returning to their homes in Iraq, and other

s proceeding to Khurasan. At the request of Sulayman Khan, who urged that the

presence of such a large gathering at such a fortified centre as Sang-Sar would

be fraught with risk, the prince decided that the party should disperse, instead,

at Firuz-K uh. I am of opinion that what his tongue professes, his heart does

not believe at all." Quddus, who shared his view, bade his companions disperse

that very night, and stated that he himself would soon proceed to Barfurush. They

hastened to implore him not to separate himself from them, and begged to be allowed

to continue to enjoy the blessings of his companionship. He counselled them to

be calm and patient, and assured them that, whatever afflictions the future might

yet reveal, they would m eet again. "Weep not," were his parting words; "the reunion

which will follow this separation

At daybreak a messenger ar rived, summoning Mirza

Muhammad-Baqir to the presence of the prince. With the consent of Quddus, he responded

to that invitation, and returned an hour later, informing his chief that the prince

had, in the presence of Sulayman Khan-i-Afshar, reiterat ed the assurances he

had given, and had treated him with great consideration and kindness. "`My oath,'

he assured me," Mirza Muhammad-Baqir explained, "`is irrevocable and sacred.'

He cited the case of Ja'far-Quli Khan, who, notwithstanding his sha meless massacre

of thousands of soldiers of the imperial army, in the course of the insurrection

fomented by the Salar, was pardoned by his sovereign and promptly invested with

fresh honours by Muhammad Shah. To-morrow the prince intends to accompany you

in the morning to the public bath, from whence he will proceed to your tent, after

which he will provide the horses required to convey the entire company to Sang-Sar,

from where they will disperse, some returning to their homes in Iraq, and other

s proceeding to Khurasan. At the request of Sulayman Khan, who urged that the

presence of such a large gathering at such a fortified centre as Sang-Sar would

be fraught with risk, the prince decided that the party should disperse, instead,

at Firuz-K uh. I am of opinion that what his tongue professes, his heart does

not believe at all." Quddus, who shared his view, bade his companions disperse

that very night, and stated that he himself would soon proceed to Barfurush. They

hastened to implore him not to separate himself from them, and begged to be allowed

to continue to enjoy the blessings of his companionship. He counselled them to

be calm and patient, and assured them that, whatever afflictions the future might

yet reveal, they would m eet again. "Weep not," were his parting words; "the reunion

which will follow this separation

The prince failed to redeem

his promise. Instead of joining Quddus in his tent, he called him, with several

of his companions, to his headquarters, and informed him, as soon as they reached

th e tent of the Farrash-Bashi,(1) that he himself would summon

him at noon to his presence. Shortly after, a number of the prince's attendants

went and told the rest of the companions that Quddus permitted them to join him

at the army's headquarters. Several of them were deceived by this report, were

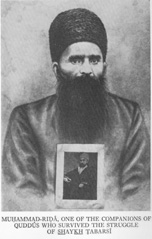

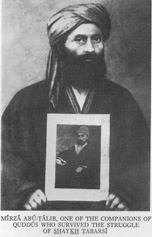

made captives, and were eventually sold as slaves. These unfortunate victims constitute

the remnant of the companions of the fort of Sha ykh Tabarsi, who survived that

heroic struggle and were spared to transmit to their countrymen the woeful tale

of their sufferings and trials.

The prince failed to redeem

his promise. Instead of joining Quddus in his tent, he called him, with several

of his companions, to his headquarters, and informed him, as soon as they reached

th e tent of the Farrash-Bashi,(1) that he himself would summon

him at noon to his presence. Shortly after, a number of the prince's attendants

went and told the rest of the companions that Quddus permitted them to join him

at the army's headquarters. Several of them were deceived by this report, were

made captives, and were eventually sold as slaves. These unfortunate victims constitute

the remnant of the companions of the fort of Sha ykh Tabarsi, who survived that

heroic struggle and were spared to transmit to their countrymen the woeful tale

of their sufferings and trials.  Soon after, the prince's attendants brought

pressure to bear u pon Mulla Yusuf to inform the remainder of his companions of

the desire of Quddus that they immediately disarm. "What is it that you will tell

them exactly?" they asked him, as he was being conducted to a place at some distance

from the army's headqu arters. "I will," was the bold reply, "warn them that whatever

be henceforth the nature of the message you choose to deliver to them on behalf

of their leader, that message is naught but downright falsehood." These words

had hardly escaped his lips when he was mercilessly put to death.

Soon after, the prince's attendants brought

pressure to bear u pon Mulla Yusuf to inform the remainder of his companions of

the desire of Quddus that they immediately disarm. "What is it that you will tell

them exactly?" they asked him, as he was being conducted to a place at some distance

from the army's headqu arters. "I will," was the bold reply, "warn them that whatever

be henceforth the nature of the message you choose to deliver to them on behalf

of their leader, that message is naught but downright falsehood." These words

had hardly escaped his lips when he was mercilessly put to death.  From this savage act they turned their attention

to the fort, plundered it of its contents, and proceeded to bombard and demolish

it completely.(2) They then

immediately encompassed the remaining companions and opened fire upon them. Any

who escaped the bullets were killed by the swords of the officers and the spears

of their men.(3) In the

From this savage act they turned their attention

to the fort, plundered it of its contents, and proceeded to bombard and demolish

it completely.(2) They then

immediately encompassed the remaining companions and opened fire upon them. Any

who escaped the bullets were killed by the swords of the officers and the spears

of their men.(3) In the

As soon as these atrocities hath been perpetrated, the prince ordered

those who had been retained as captives to be ushered, one after another, into

his presence. Those among them who were men of recognised standing,

such as the father of Badi',(1) Mulla Mirza Muhammad-i-Furughi,

and Haji Nasir-i-Qazvini,(2) he charged his attendants to conduct to Tihran and obtain

in return for their deliverance a ransom from each one of them in direct proportion

to their capacity and wealth. As to the rest, he gave order s to his executioners

that they be immediately put to death. A few were cut to pieces with the sword,(3) others were torn asunder, a number were bound to trees

and riddled with bullets, and still other s were blown

As soon as these atrocities hath been perpetrated, the prince ordered

those who had been retained as captives to be ushered, one after another, into

his presence. Those among them who were men of recognised standing,

such as the father of Badi',(1) Mulla Mirza Muhammad-i-Furughi,

and Haji Nasir-i-Qazvini,(2) he charged his attendants to conduct to Tihran and obtain

in return for their deliverance a ransom from each one of them in direct proportion

to their capacity and wealth. As to the rest, he gave order s to his executioners

that they be immediately put to death. A few were cut to pieces with the sword,(3) others were torn asunder, a number were bound to trees

and riddled with bullets, and still other s were blown

This terrible butchery had hardly been concluded when three of the compa

nions of Quddus, who were residents of Sang-Sar, were ushered into the presence

of the prince. One of them was Siyyid Ahmad, whose father, Mir Muhammad-'Ali,

a devoted admirer of Shaykh Ahmad-i-Ahsa'i, had been a man of great learning and

distinguish ed merit. He, accompanied by this same Siyyid Ahmad and his brother,

Mir Abu'l-Qasim, who met his death the very night on which Mulla Husayn was slain,

had departed for Karbila in the year preceding the declaration of the Bab, with

the intention of i ntroducing his two sons to Siyyid Kazim. Ere his arrival, the

siyyid had departed this life. He immediately determined to leave for Najaf. While

in that city, the Prophet Muhammad one night appeared to him in a dream, bidding

the Imam Ali, the Com mander of the Faithful, announce to him that after his death

both his sons, Siyyid Ahmad and Mir Abu'l-Qasim, would attain the presence of

the promised Qa'im and would each suffer martyrdom in His path. As soon as he

awoke, he called for his son Siyy id Ahmad and acquainted him with his will and

last wishes. On the seventh day after that dream he died.

This terrible butchery had hardly been concluded when three of the compa

nions of Quddus, who were residents of Sang-Sar, were ushered into the presence

of the prince. One of them was Siyyid Ahmad, whose father, Mir Muhammad-'Ali,

a devoted admirer of Shaykh Ahmad-i-Ahsa'i, had been a man of great learning and

distinguish ed merit. He, accompanied by this same Siyyid Ahmad and his brother,

Mir Abu'l-Qasim, who met his death the very night on which Mulla Husayn was slain,

had departed for Karbila in the year preceding the declaration of the Bab, with

the intention of i ntroducing his two sons to Siyyid Kazim. Ere his arrival, the

siyyid had departed this life. He immediately determined to leave for Najaf. While

in that city, the Prophet Muhammad one night appeared to him in a dream, bidding

the Imam Ali, the Com mander of the Faithful, announce to him that after his death

both his sons, Siyyid Ahmad and Mir Abu'l-Qasim, would attain the presence of

the promised Qa'im and would each suffer martyrdom in His path. As soon as he

awoke, he called for his son Siyy id Ahmad and acquainted him with his will and

last wishes. On the seventh day after that dream he died.  In Sang-Sar two other persons, Karbila'i Ali and

Karbila'i Abu-Muhammad, both known for their piety a nd spiritual insight, strove

to prepare the people for the acceptance of

In Sang-Sar two other persons, Karbila'i Ali and

Karbila'i Abu-Muhammad, both known for their piety a nd spiritual insight, strove

to prepare the people for the acceptance of

These two sons of Karbila'i Abu- Muhammad were

the two companions who had been ushered, together with Siyyid Ahmad, into the

presence of the prince. Mulla Zaynu'l-'Abidin- i-Shahmirzadi, one of the trusted

and learned counsellors of the government, acquainted the prince with their story

and related the experiences and activities of their respective fathers. "For what

reason," Siyyid Ahmad was asked, "have you chosen to tread a path that has involved

you and your kinsmen in such circumstances of wretchedness and disgrace? Could

you not have been satisfied with the vast number of erudite and ill ustrious divines

who are to be found in this land and in Iraq?" "My faith in this Cause," he fearlessly

retorted, "is born not of idle imitation. I have dispassionately enquired into

its precepts, and am convinced of its truth. When in Najaf, I ven tured to request

the preeminent mujtahid of that city, Shaykh Muhammad-Hasan-i-Najafi, to expound

for me certain truths connected with the secondary principles underlying the teachings

of Islam. He refused to accede to my request. I reiterated my ap peal, whereupon

he angrily rebuked me and persisted in his refusal. How can I, in the light of

such experience, be expected to seek enlightenment on the abstruse articles of

the Faith

These two sons of Karbila'i Abu- Muhammad were

the two companions who had been ushered, together with Siyyid Ahmad, into the

presence of the prince. Mulla Zaynu'l-'Abidin- i-Shahmirzadi, one of the trusted

and learned counsellors of the government, acquainted the prince with their story

and related the experiences and activities of their respective fathers. "For what

reason," Siyyid Ahmad was asked, "have you chosen to tread a path that has involved

you and your kinsmen in such circumstances of wretchedness and disgrace? Could

you not have been satisfied with the vast number of erudite and ill ustrious divines

who are to be found in this land and in Iraq?" "My faith in this Cause," he fearlessly

retorted, "is born not of idle imitation. I have dispassionately enquired into

its precepts, and am convinced of its truth. When in Najaf, I ven tured to request

the preeminent mujtahid of that city, Shaykh Muhammad-Hasan-i-Najafi, to expound

for me certain truths connected with the secondary principles underlying the teachings

of Islam. He refused to accede to my request. I reiterated my ap peal, whereupon

he angrily rebuked me and persisted in his refusal. How can I, in the light of

such experience, be expected to seek enlightenment on the abstruse articles of

the Faith

Meanwhile Mirza Muhammad-Taqi, accompanied

by seven of the ulamas of Sari, set out from that town to share in the meritorious

act of inflicting the punishment of death upon the companions of Quddus. When

they found that they had already been put to death, Mirza Muhammad-Taqi urged

the prince to reconside r his decision and to order the immediate execution of

Siyyid Ahmad, pleading that his arrival at Sari would be the signal for fresh

disturbances as grave as those which had already afflicted them. The prince eventually

yielded, on the express condit ion that he be regarded as his guest until his

own arrival at Sari, at which time he would take whatever measures were required

to prevent him from disturbing the peace of the neighbourhood.

Meanwhile Mirza Muhammad-Taqi, accompanied

by seven of the ulamas of Sari, set out from that town to share in the meritorious

act of inflicting the punishment of death upon the companions of Quddus. When

they found that they had already been put to death, Mirza Muhammad-Taqi urged

the prince to reconside r his decision and to order the immediate execution of

Siyyid Ahmad, pleading that his arrival at Sari would be the signal for fresh

disturbances as grave as those which had already afflicted them. The prince eventually

yielded, on the express condit ion that he be regarded as his guest until his

own arrival at Sari, at which time he would take whatever measures were required

to prevent him from disturbing the peace of the neighbourhood.  No sooner had M irza Muhammad-Taqi taken the direction

of Sari than he proceeded to vilify Siyyid Ahmad and his father. "Why ill-treat

a guest," his captive pleaded, "whom the prince has committed to your charge?

Why ignore the Prophet's injunction, `Honour thy gue st though he be an infidel'?"

Roused to a burst of fury, Mirza Muhammad-Taqi,

No sooner had M irza Muhammad-Taqi taken the direction

of Sari than he proceeded to vilify Siyyid Ahmad and his father. "Why ill-treat

a guest," his captive pleaded, "whom the prince has committed to your charge?

Why ignore the Prophet's injunction, `Honour thy gue st though he be an infidel'?"

Roused to a burst of fury, Mirza Muhammad-Taqi,

As soon as his work was completed, the prince, accompanied by Quddus,

returned to Barfurush. They arrived on Friday afternoon, the eighteenth of Jamadiyu'th-Thani.(1) The Sa'idu'l-'Ulama', together with all the ulamas of

the town, came out to welcome the prince and to extend their congratulations on

his triumphal return. The whole town was beflagged to celebrate the victory ,

and the bonfires which blazed at night witnessed to the joy with which a grateful

population greeted the return of the prince. Three days of festivities elapsed

during which he gave no indication as to his intention regarding the fate of Quddus.

H e vacillated in his policy, and was extremely reluctant to ill-treat his captive.

He at first refused to allow the people to gratify their feelings of unrelenting

hatred, and was able to restrain their fury. He had originally intended to conduct

him to Tihran and, by delivering him into the hands of his sovereign, to relieve

himself of the responsibility which weighed upon him.

As soon as his work was completed, the prince, accompanied by Quddus,

returned to Barfurush. They arrived on Friday afternoon, the eighteenth of Jamadiyu'th-Thani.(1) The Sa'idu'l-'Ulama', together with all the ulamas of

the town, came out to welcome the prince and to extend their congratulations on

his triumphal return. The whole town was beflagged to celebrate the victory ,

and the bonfires which blazed at night witnessed to the joy with which a grateful

population greeted the return of the prince. Three days of festivities elapsed

during which he gave no indication as to his intention regarding the fate of Quddus.

H e vacillated in his policy, and was extremely reluctant to ill-treat his captive.

He at first refused to allow the people to gratify their feelings of unrelenting

hatred, and was able to restrain their fury. He had originally intended to conduct

him to Tihran and, by delivering him into the hands of his sovereign, to relieve

himself of the responsibility which weighed upon him.  The

Sa'idu'l-'Ulama''s unquenchable hostility, however, interfered with t he execution

of this plan. The hatred with which Quddus and his Cause inspired him blazed into

furious rage as he witnessed the increasing evidences of the prince's inclination

to allow so formidable an opponent to slip from his grasp. Day and night he remonstrated

with him and, with every cunning that his resourceful brain could devise, sought

to dissuade him from pursuing a policy which he thought to be at once disastrous

and cowardly. In the fury of his despair, he appealed to the mob and so ught,

by inflaming their passions, to awaken the basest sentiments of revenge in their

hearts. The whole of Barfurush had been aroused by the persistency of his call.

His diabolical skill

The

Sa'idu'l-'Ulama''s unquenchable hostility, however, interfered with t he execution

of this plan. The hatred with which Quddus and his Cause inspired him blazed into

furious rage as he witnessed the increasing evidences of the prince's inclination

to allow so formidable an opponent to slip from his grasp. Day and night he remonstrated

with him and, with every cunning that his resourceful brain could devise, sought

to dissuade him from pursuing a policy which he thought to be at once disastrous

and cowardly. In the fury of his despair, he appealed to the mob and so ught,

by inflaming their passions, to awaken the basest sentiments of revenge in their

hearts. The whole of Barfurush had been aroused by the persistency of his call.

His diabolical skill

No sooner had the ulamas assembled than the

prince gave orders for Qudd us to be brought into their presence. Since the day

of his abandoning the fort, Quddus, who had been delivered into the custody of

the Farrash-Bashi, had not been summoned to his presence. As soon as he arrived,

the prince arose and invited him to b e seated by his side. Turning to the Sa'idu'l-'Ulama',

he urged that his conversations with him be dispassionately and conscientiously

conducted. "Your discussions," he asserted, "must revolve around, and be based

upon, the verses of the Qur'an and the traditions of Muhammad, by which means

alone you can demonstrate the truth or falsity of your contentions." "For what

reason," the Sa'idu'l-'Ulama' impertinently enquired, "have you, by choosing to

place a green turban upon your head, arrogated to yourself a right which only

he who is a true descendant of the Prophet can claim? Do you not know that whoso

defies this sacred tradition is accursed of God?" "Was Siyyid Murtada," Quddus

calmly replied, "whom all the recognised ulamas praise and esteem, a descendant

of

No sooner had the ulamas assembled than the

prince gave orders for Qudd us to be brought into their presence. Since the day

of his abandoning the fort, Quddus, who had been delivered into the custody of

the Farrash-Bashi, had not been summoned to his presence. As soon as he arrived,

the prince arose and invited him to b e seated by his side. Turning to the Sa'idu'l-'Ulama',

he urged that his conversations with him be dispassionately and conscientiously

conducted. "Your discussions," he asserted, "must revolve around, and be based

upon, the verses of the Qur'an and the traditions of Muhammad, by which means

alone you can demonstrate the truth or falsity of your contentions." "For what

reason," the Sa'idu'l-'Ulama' impertinently enquired, "have you, by choosing to

place a green turban upon your head, arrogated to yourself a right which only

he who is a true descendant of the Prophet can claim? Do you not know that whoso

defies this sacred tradition is accursed of God?" "Was Siyyid Murtada," Quddus

calmly replied, "whom all the recognised ulamas praise and esteem, a descendant

of

No one dared to contradict h im. The Sa'idu'l-'Ulama'

burst forth into a fit of indignation and despair. Angrily he flung his turban

to the ground and arose to leave the meeting. "This man," he thundered, ere he

departed, "has succeeded in proving to you that he is a descenden t of the Imam

Hasan. He will, ere long, justify his claim to be the mouthpiece of God and the

revealer of His will!" The prince was moved to make this declaration: "I wash

my hands of all responsibility for any harm that may befall this man. You are

free to do what you like with him. You will yourselves be answerable to God on

the Day of Judgment." Immediately after he had spoken these words, he called for

his horse and, accompanied by his attendants, departed for Sari. Intimidated by

the imprecations of the ulamas and forgetful of his oath, he abjectly surrendered

Quddus to the hands of an unrelenting foe, those ravening wolves who panted for

the moment when they could pounce, with uncontrolled violence, upon their prey,

and let loose on him the fiercest passions of revenge and hate.

No one dared to contradict h im. The Sa'idu'l-'Ulama'

burst forth into a fit of indignation and despair. Angrily he flung his turban

to the ground and arose to leave the meeting. "This man," he thundered, ere he

departed, "has succeeded in proving to you that he is a descenden t of the Imam

Hasan. He will, ere long, justify his claim to be the mouthpiece of God and the

revealer of His will!" The prince was moved to make this declaration: "I wash

my hands of all responsibility for any harm that may befall this man. You are

free to do what you like with him. You will yourselves be answerable to God on

the Day of Judgment." Immediately after he had spoken these words, he called for

his horse and, accompanied by his attendants, departed for Sari. Intimidated by